Which way is the best, and how, to overcome loneliness?

Take the UCLA Loneliness Test and discover research-backed strategies to quickly overcome loneliness and boost your happiness for a healthier more fulfilling life.

I hope you are keeping well and regardless of the US Election result last week, returning to ‘normal life’. [Ed. This post is being published months later, see Whichwayhow to conquer procrastination ] A Native American Indian once said, “I woke up the next day and the land of my country was still the same,” referring to the beautiful mountains, rivers and landscapes.

Anyone who has travelled in America, like I have, will know the truth in this. I grew up in London, in the UK, watching Westerns, with Sierra Leone’s breathtaking vistas, and in real life, they are even more spectacular, something every American can rightly be proud of.

It is very hard when you come from a small island over the pond, like ours, to appreciate the scale of the U.S., there is so much space. But whether you’re in the middle of the wilderness, or a big city, you can equally be affected by loneliness, which is the subject of this fortnight’s deep-dive because I have found myself being lonely recently, too. I was shocked when I measured it, which you can do yourself in this post, see below. And this free post may increase your life expectancy by over 25% if you are lonely, too, and use the strategies suggested to overcome it.

Which may make this a good time to ask you to subscribe for free not to miss other investigative posts every fortnight like Whichwayhow Breathwork, Whichwayhow Meditation, Whichwayhow to be a hero and Whichwayhow reversing cavities.

Words: 3478

Reading Time: 15mins

Key Findings

1) The mortality impact of loneliness is equivalent to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

2) The best way of measuring your loneliness is the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale.

3) Loneliness has 3 dimensions: Intimate loneliness; Relational Loneliness; and Collective Loneliness.

4) The 4 best coping strategies are: Changing one’s desired level of social contact; Achieving higher levels of social contact; Minimising loneliness; and Therapeutic Interventions.

5) Research showed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to be the most effective therapeutic treatment.

CONTENTS

1. What is the definition, prevalence, and human and societal cost of loneliness?

2. How do you know if you’re lonely?

3. The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale

4. Interpreting Results on the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale

5. What are my loneliness scores?

7. Which is the best way to cure loneliness?

8. Why was CBT the most effective therapeutical method for curing loneliness?

9. Conclusion

1. What is the definition, prevalence, and human and societal cost of loneliness?

Loneliness is a hot topic in the mass media right now, with the New York Times recently publishing, “Why is the Loneliness Epidemic So Hard to Cure?” (28 August 2024), “The Loneliness Curve” (21 May 2024), and “Loneliness Can Change the Brain” (13 May 2024). All unfortunately behind a paywall, but you get the point!

Ironically, you are not alone. Loneliness affects over half the US population, and interestingly, is more common among parents than non-parents:

“About 65% of parents and guardians are classified as lonely, a 10-point gap compared to non-parents (55%)”[1]

In 2023, loneliness and the lack of social connection was considered such a health risk, the Surgeon General Vivek Murphy published, “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,”[2] which claimed the mortality impact of loneliness and lack of social connection is equivalent to smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, worse than obesity and physical inactivity combined.

And loneliness and social isolation “increase the risk for premature death by 26% and 29% respectively.”

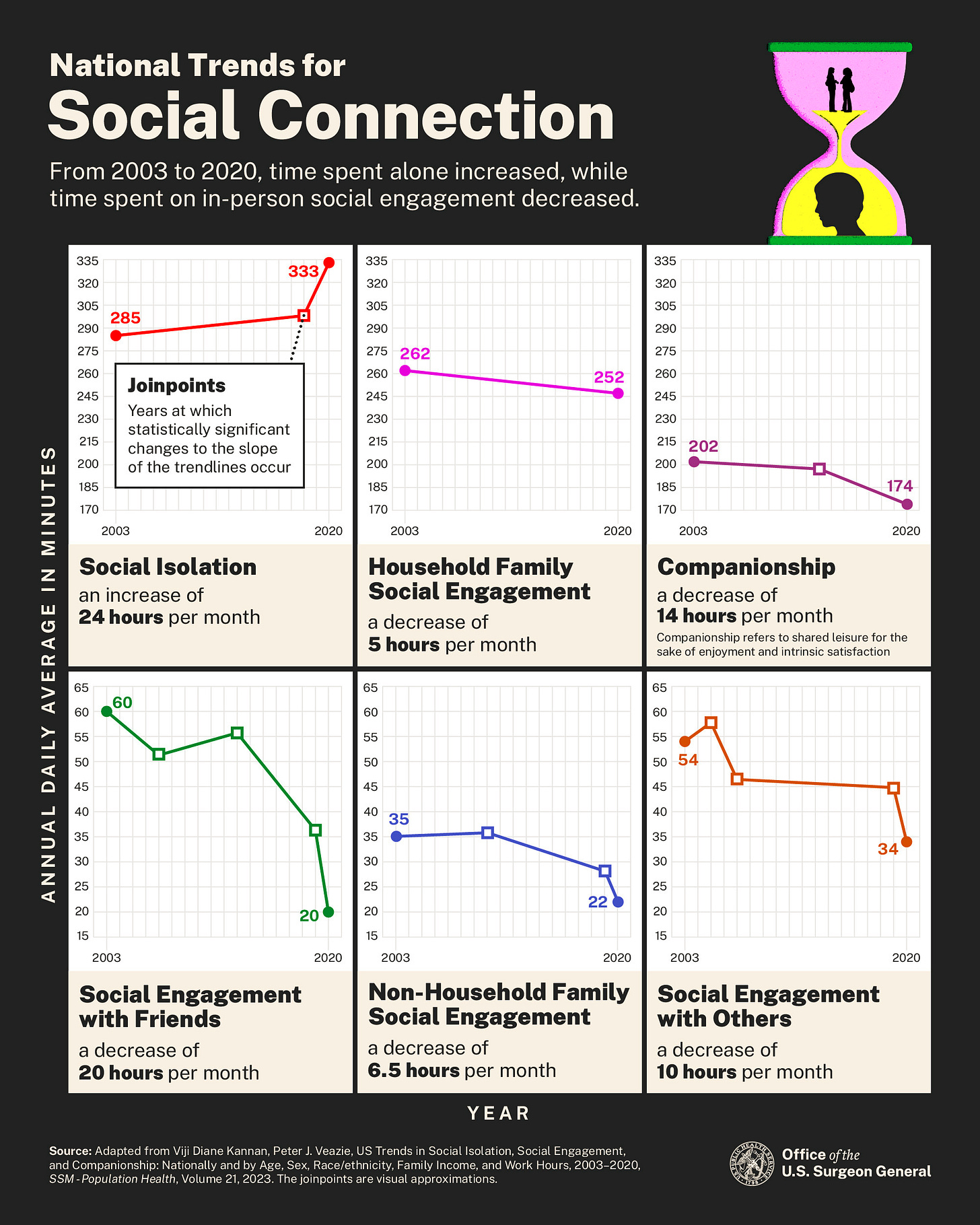

Below you can see graphically in the National Trends for Social Connection how the time we spend alone has increased for Social Isolation (+24hrs/month), and decreased for social engagement: Household family (-5hrs/month); Companionship (-14hrs/month); with Friends (-20hrs/month); Non-family (-6.5hrs/month); and with Others (-10hrs/months), from 2003 to 2020, in the US.

Further the cost of social isolation is estimated at $6.7bn in excess Medicare spending, and stress-related absenteeism due to loneliness estimated to cost employers $153bn annually.

Loneliness has been defined as “a subjective negative experience that results from inadequate meaningful connections, where ‘inadequate’ refers to the discrepancy or unmet need between an individual’s preferred and actual experience.”[3] Further, it is considered a “fundamental human need, as essential as food, water and shelter.”

In the UK, the government adopted a similar, but perhaps slightly clearer, definition drawing on Perlman and Peplau and used by the Campaign to End Loneliness and the Jo Cox Commission: “a subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.”[4] This is important because it implies our expectations influence our perception of loneliness, as we shall see later.

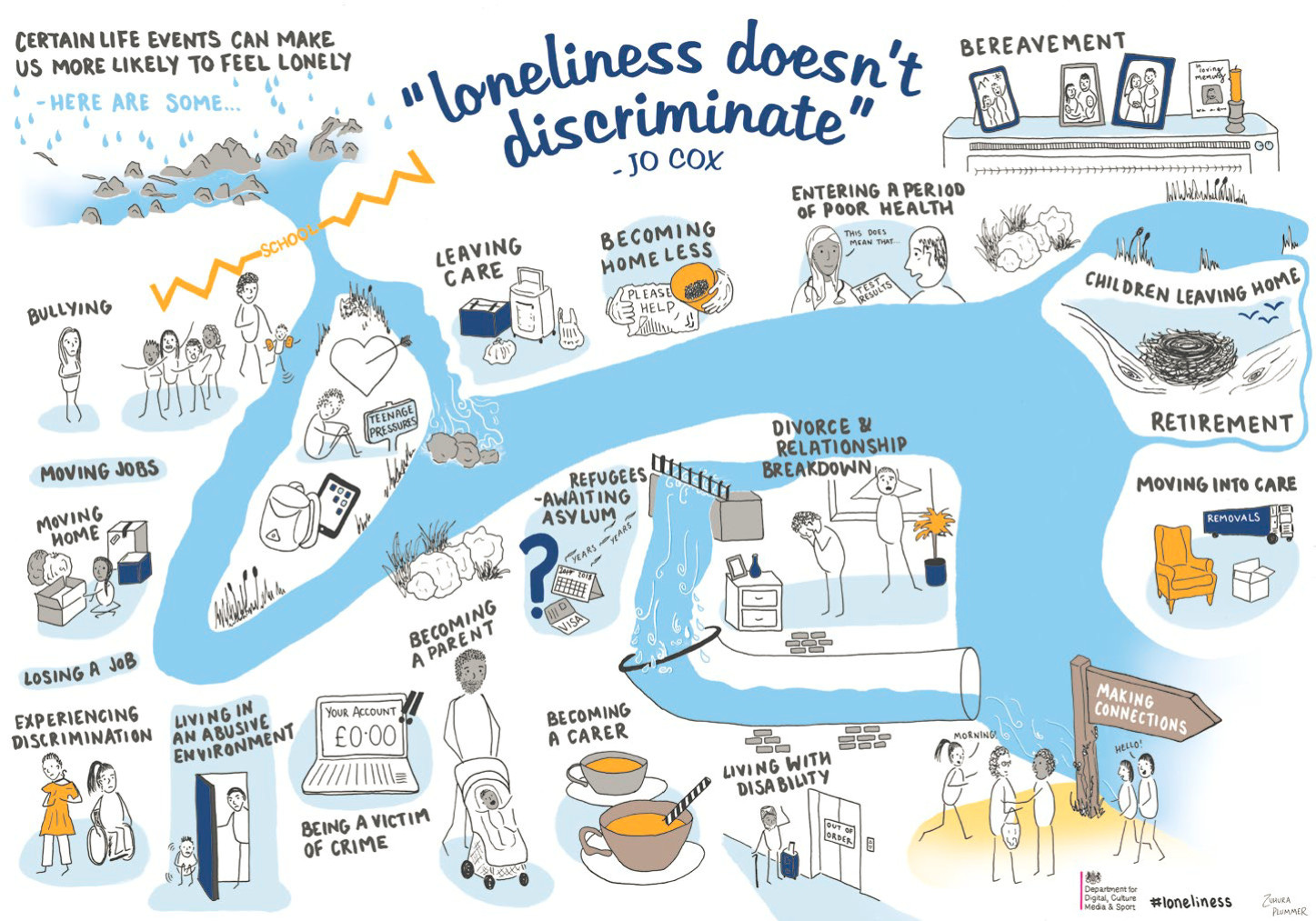

It is important to bear in mind that “loneliness doesn’t discriminate” – Jo Cox, and certain life events may make us feel lonely sometimes, see figure below, and therefore it is natural. Although perhaps we can always learn to cope with loneliness better.

But how do we know if we’re lonely?

2. How do you know if you’re lonely?

It is hard to know if you are lonely, precisely because, like the definition states, it is a subjective experience. However, Russell et al., (1980) devised a reliable and validated questionnaire which you can use to test yourself, like I have done, which I share, below.

It may be worth doing this questionnaire twice, once before you have read the whole article, to analyse the type and extent of your loneliness, and inform your consideration of the best way of dealing with it in the suggested interventions that follow. And, again, after you have chosen and implemented strategies for reducing loneliness, after a few months, to see if your score has improved.

3. The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale[5]

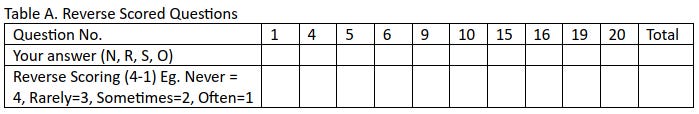

Directions: Indicate how often you feel the way described in each of the following statements. Circle one number for each.

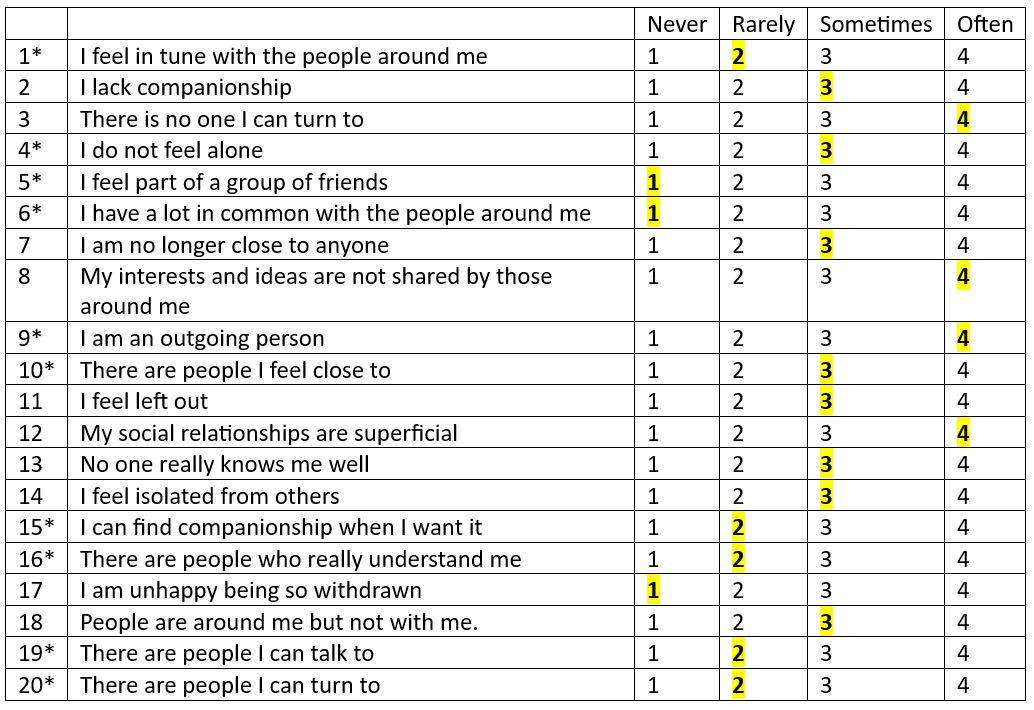

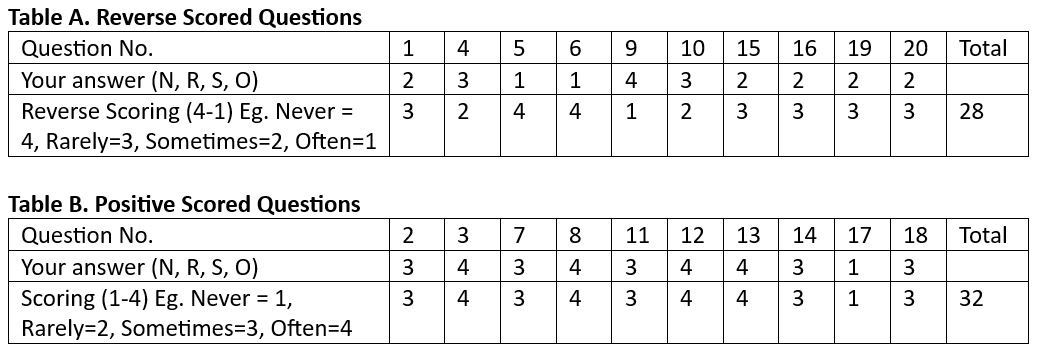

To score yourself on this test use the following table:

4. Interpreting Results on the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale

Range 20 to 80.

“The cut-offs for loneliness severity were adapted from the report by Cacioppo and Patrick (2008) as follows:

Total score <28 = no/low loneliness

Total score 28 to 43 = moderate loneliness

Total score >43 = high loneliness.” [6]

5. What are my loneliness scores?

Here are my results on the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale:

Table A Total (28) + Table B Total (32) = 60/80

Total score <28 = no/low loneliness

Total score 28 to 43 = moderate loneliness

Total score >43 = high loneliness.

Therefore, according to my results, I was right, I have a relatively high degree of loneliness, which is consistent with my subjective perception, although, frankly, I didn’t expect it to be that high!

6. What causes loneliness?

Firstly, it should be noted that loneliness can be a fleeting feeling, which many of us may have from time to time, but we should pay more attention when it lasts for a few days or more, or doesn’t ever seem to go away.

There are three dimensions of loneliness: Intimate loneliness; Relational loneliness; and Collective loneliness, which match the three dimensions surrounding one’s attentional space: Intimate space (personal space); Social space (friends and family); and Public space. [7]

6.1 Intimate loneliness

Also known as emotional loneliness, refers to the absence of someone we rely on for emotional support, like a partner or close friend. It will come as no surprise that a study by Hawkley et al, 2005, found that the best (negative) predictor of intimate loneliness was a good marriage.

“Education and income were negatively associated with loneliness and explained racial/ethnic differences in loneliness. Being married largely explained the association between income and loneliness, with positive marital relationships offering the greatest degree of protection against loneliness. Independent risk factors for loneliness included male gender, physical health symptoms, chronic work and/or social stress, small social network, lack of a spousal confidant, and poor-quality social relationships.”[8]

This relates to “Isolation” questions in the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17 and 18.[9] Look back at your answers, and if you scored higher on these questions, it may suggest your loneliness may be due to lacking in this dimension.

6.2 Relational loneliness.

Also known as social loneliness, refers to the perceived presence or absence of quality friendships or social relationships, within one’s relational or social space. Importantly, this relational space is defined as multi-modal (visual, auditory and tactile) allowing for face-to-face communications. However, it is not the quantity of friends that matters, but rather the quality of those friendships, and tends to “play a slightly greater role in influencing loneliness in women than men”.

This relates to “Relational Connectedness” questions in the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: 10, 15, 16, 19 and 20. Again, look back at your answers, and if you scored higher on these questions, it may suggest your loneliness may be due to lacking in this dimension.

6.3 Collective loneliness

This refers to our valued social identities within society, like our work, school or team, or any active networks we maintain, in a public space, like volunteering, and tends to be “slightly more heavily weighted in men than women.”

This relates to “Collective Connectedness” questions in the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: 1, 5, 6, 9.

Again, look back at your answers, and if you scored higher on these questions, it may suggest your loneliness may be due to lacking in this dimension.

Which begs the question, what does research have to show about the best way to cure loneliness? Before I consider how I cured loneliness.

7. Which is the best way to cure loneliness?

There are four coping strategies that research has suggested may be effective: Changing one’s desired level of social contact; Achieving higher levels of social contact; Minimising loneliness; and Therapeutic Interventions.[10] Let’s briefly consider each one.

7.1 Changing one’s desired level of social contact

7.1.1 Adaptation. Over time we may adapt our expectations of social contact, and while not condoning this as a solution, Weiss (1973) noted that lonely people may "change their standards for appraising their situations and feelings, and, in particular, that standards might shrink to conform more closely to the shape of bleak reality."

7.1.2 Task Choice. By choosing tasks that we prefer to do alone, like, say, reading, writing or going to the gym, we may avoid feelings of loneliness by doing tasks that we normally prefer to do with others, say, going to the cinema. Robert Brown (1979) studied hermits, and found they had many activities they enjoyed doing alone. And other researchers have found doing more solitary activities you enjoy can reduce loneliness.

7.1.3 Changing standards. Finally, we may be able to reduce our desired level of social contact, by changing our standards of who is acceptable as a friend. We may be our own worst enemy, in this regard, by unintentionally making ‘enemies’ of potential friends because we are scared to trust again.

None of us want to be hurt again, but projecting that judgment on others, albeit defensively, may, ironically, hurt us more, and not necessarily be a valid conclusion, either, as we shall consider in the ‘loneliness cycle’ below.

7.2 Achieving higher levels of social contact

The most common perception of reducing loneliness in a UCLA study was to find a girlfriend/boyfriend. But there are many other ways of increasing social contact, such as joining clubs, evening classes, starting conversations with other people and deepening relationships with existing acquaintances. Rubenstein and Shaver (1980) found that loneliness is reduced by visiting, or even just calling, a friend.

7.3 Minimising Loneliness

Another way to reduce loneliness is to change your perception of the gap between the social interaction we desire and have. You could deny the gap, or consider that other objectives in life are more important, or re-interpret it as a learning opportunity.

If self-esteem is threatened by loneliness, one could boost one’s self-esteem in non-social ways. Unfortunately, some may do this by resorting to alcohol or drug use, and if you are struggling with alcohol, you may find my book on ways to control or quit your drinking helpful, here.

7.4 Therapeutic interventions

A quantitative literature review[11] by Masi et al.’s (2011) found no evidence for better efficacy of one-to-one individual therapies than group therapies, in spite of previous studies claiming the contrary.

And the results of the four primary types of intervention program that were analysed to reduce loneliness were mostly not found to be effective, except for one:

1) Social recreation intervention (increasing opportunities for social contact) (-0.62) not found to be effective.

2) Social support intervention (mentoring programs, buddy-care program, conference calls) Significant but small reduction in loneliness (-0.162)

3) Social skills intervention (speaking on the phone, giving and receiving compliments, enhancing non-verbal communication skills (-0.17) not found to be effective in reducing loneliness.

4) Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (addressing maladaptive social cognition) which had the largest effect size (-0.598).

8. Why was Cognitive Behavioral Therapy the most effective therapeutical method for curing loneliness?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy aims to challenge the automatic negative thoughts we may have about others, or social interactions, to identify any dysfunctional and irrational beliefs, false attributions, or self-defeating thoughts we may have developed, and assume are facts, but are actually unverified.

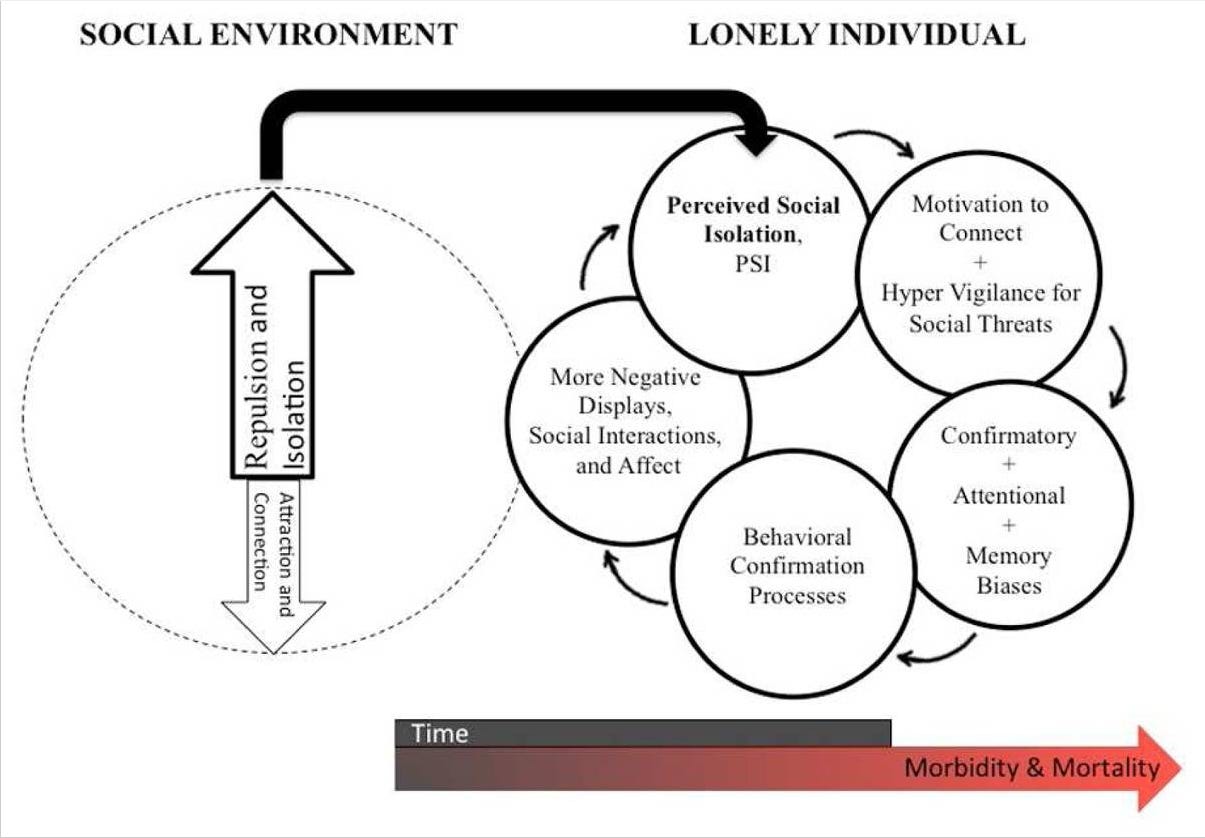

People don’t choose to be lonely, they find themselves at one end of the spectrum of social connections and feel isolated [Perceived Social Isolation (PSI]. Their perception that they are on the end and isolated, increases their motivation for self-preservation, which increases their desire to connect with others but also their sensitivity to social threats or rejection [Hyper-Vigilance for Social Threats]. This sensitivity can make lonely people pay more attention to negative social cues [Attentional Bias]. They might also remember negative experiences more than positive ones [Memory Bias]. Because of this, lonely people might expect social interactions to go badly [Behavioral Confirmation Bias]. This expectation can actually make interactions go worse, reinforcing withdrawal, negativity and feelings of loneliness [More Negative Displays, Social Interactions and Affect], creating a cycle of loneliness.

The good news is that there are ways to break this cycle:

Learning to see things from other people's perspectives

Practicing empathy (understanding others' feelings)

Recognizing negative thoughts about social situations and questioning if they're really true

Being more mindful (aware) in social situations (to correct confirmation bias]

Sharing positive experiences with others (Capitalization).

Research on social cognition is demonstrated in the model in the figure below, “The effects of loneliness on social cognition.”

9. Conclusion

If you are feeling lonely, the first thing to do is remember you are not alone, many people feel like this from time to time, like half the population of the U.S., including this author! When we feel lonely, I know, it is hard to picture millions of us feeling exactly the same way right now. But there are, and my heart goes out to all of you, which is why I wrote this.

Secondly, your feelings of loneliness are valid, and you shouldn’t be hard on yourself, or more importantly, blame anyone else for them, like friends or old friends, partners or ex-partners, because that will only engage you in the loneliness cycle, described above, and even threaten to trap you in it, which makes getting out of it more difficult. There is a lot to be said for forgiveness and acceptance, without getting too spiritual about it.

Thirdly, we all sometimes need to work on ourselves, which is why the UCLA Loneliness Scale is so useful, but you have to take the time and effort to complete the questionnaire and analyse the results. We don’t always have an accurate picture of our level of loneliness and, in particular, which dimensions of loneliness are most affecting us.

If we don’t know which dimensions of loneliness are affecting us, according to the research above, it may be harder to adopt the best strategy to overcome it. What worked for me, may not work for you. We are all different, and loneliness, as stated in the definition is a subjective experience.

Finally, we may have to face the fear, and embrace a solution we sometimes don’t instinctively feel comfortable with. This may be contrary to all the feel-good advice out there on loneliness, but I think it is important to be honest. Any kind of worthwhile change involves doing something differently. We can’t expect to carry on doing what we are doing, and expect the world to change to accommodate us. It doesn’t work like that, although sometimes I have to remind myself of this! I can be stubborn like a petulant child, even in my fifties!

And I know how ridiculous that sounds, but then I look at my test results in black and white, and it makes me think… To be honest, should I rush back and change all the results! But it is how you perceive the questions the first time, that has any value. And, unlike me, you don’t have to publish the results to the whole world, so you’ve got it relatively easy!

A few practical changes I made to my life, and these are personal rather than researched, were to invest in an Echo Dot and subscribe to Amazon Music Unlimited so I could listen to music while I work, but a radio app on your phone would probably do just as well. I also installed the Gemini app on my phone so I could ask AI questions verbally, which I actually found quite comforting, but there is also ChatGPT for Alexa, but you need to pay a subscription for that.

I also started attending group meditations, in addition to meditating alone (see Whichwayhow to meditate for more information). And finally, the greatest difference to my life, was making a conscious effort to spend more time with my family of an evening and on the weekends. This was tied into feeling more grateful for what I had, starting with my family (see Whichwayhow to practice gratitude for more information.)

I have just retaken the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale and I am pleased to report I scored 35, which doesn’t mean no/low loneliness, it means moderate loneliness, rather than high like it was before, so I am getting there! And I am sure you will, too.

Thank you for reading.

If this post has helped you, and if you think it might help someone else, please like and share this post.

If you don’t want to miss out on the next FREE fortnightly investigative post to brighten your day— and potentially solve your problem—subscribe for FREE below now!!!

If you don’t want to subscribe but would like to show your appreciation for this article, you can buy me a coffee here. Thanks in advance 😊

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy Whichwayhow Breathwork, Whichwayhow Meditation, Whichwayhow to be a hero and Whichwayhow reversing cavities.

I am a CBT Counsellor and if you would like professional online 1:1 support worldwide, please email me at Mark dot Holmes at Whichwayhow dot com. The first session is always free!

References

[1] Commissioned by Cigna Corporation, Morning Consult conducted a survey of 2,496 U.S. adults from December 13-19, 2021. https://newsroom.thecignagroup.com/loneliness-epidemic-persists-post-pandemic-look Accessed at 12:26 on 10th November 2024

[2] Murthy, V. (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK595227/

[3] Prohaska T, Burholt V, Burns A, et al Consensus statement: loneliness in older adults, the 21st century social determinant of health? BMJ Open 2020;10:e034967. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034967

[4] Drawing on Perlman, D. & Peplau, L. A. (1981) Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness. In R. Gilmour & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal Relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder (pp. 31-56). London: Academic Press

[5] The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminate validity evidence Sep 1980 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39(39):472-480. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

[6] Lee C, Cho B, Yang Q, et al. A Psychometric Analysis of the 20-item Revised University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Among Korean Older Adults Living Alone. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2021;14(6):306-316. doi:10.3928/19404921-20210924-03

[7] Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015 Mar;10(2):238-49. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. PMID: 25866548; PMCID: PMC4391342.

[8] Hawkley LC, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Masi CM, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008 Nov;63(6):S375-84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375. PMID: 19092047; PMCID: PMC2769562.

[9] Hawkley LC, Gu Y, Luo YJ, Cacioppo JT. The mental representation of social connections: generalizability extended to Beijing adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044065. Epub 2012 Sep 11. PMID: 23028486; PMCID: PMC3442957.

[10] Perlman, Daniel & Peplau, Letitia. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness Personal relationships 3. Personal relationships in disorder. 3. 31-43.

[11] Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15:219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[12] Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015 Mar;10(2):238-49. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. PMID: 25866548; PMCID: PMC4391342.