Which way is the best, and how, to conquer procrastination?

Proven Strategies for Overcoming Delay Tactics. Why do I always find something better to do than what I really need to do right now? And using AI to overcome procrastination. You can do it! Here’s how

Although many US presidents have been accused of procrastination[1], this is the last thing you could accuse Donald Trump of, having hit the ground running on the first day of his inauguration as 47th President signing twelve executive orders ranging from ending birthright citizenship to leaving the World Health Organisation to declaring national energy and border emergencies[2], which made me wonder why I kept on postponing actually writing about procrastination?

Yes, I have been procrastinating about returning to writing this blog after a three-month hiatus due to cataract surgery (subscribe for free not to miss WWH Cataracts coming soon—hopefully!) but if I am really honest, it only took six weeks to recover from surgery, and the rest is months of procrastination.

My last post was on 30th October 2024 and then I had a post on Gratitude lined up for Thanksgiving, which I only managed to start and never finish, another on Loneliness for Christmas, which I never managed to finish either, and I didn’t really know why, and it is now 5th March 2025.

Procrastination lurked below my radar in the shadows, like a self-defeating phantom. The saddest thing is the weight I had to carry while ostensibly doing ‘other’ things, and this constant nagging stress of having things undone. I didn’t know which way to look for the best; I was every which way but loose!

It’s not like I could afford to take time off work either. One look at my bank balance would be enough to shock Frankenstein back to life! (And another thing, why does my bank have to add salt to injury by stating my mortgage account balance below my current account balance? It’s like falling in the crevasse and seeing the abyss below! That’s just mean(!) Or maybe I’m already looking to blame someone else for my procrastination! (Or looking for more excuses not to write about it! Sorry!!!)

The opportunity cost of procrastination is obviously the money I might have earnt from paid subscriptions, never mind the loss of paid subscribers, but there is also the moral cost to my free subscribers. Don’t I care about letting them down?

Of course, I do. I hate being like this. I loved researching and writing my fortnightly posts and the excitement of hitting publish and feeling that sense of accomplishment. What went wrong?

I am fed up of constantly doing almost anything but writing: I have hung new curtains in my office; replaced the door handle in the lounge; installed a CCTV camera; cleaned my desk; replaced my laptop keyboard; darned a shirt and pair of trousers… And, OK, it pains me to say, and I feel terribly guilty for admitting this, reached Level 23 on Fallout 76 on my Xbox!

It hurts. It is akin to self-destruction. An overwhelming crisis of inaction and indecision. Am I mentally unwell? Is it just me? For heaven’s sake, why did I start procrastinating and what is the cure?

If you’re anything like me and this has happened to you, don’t worry, I’ve finally researched this issue so you don’t have to, and discovered which is the best way, and how, to avoid procrastination from the best scientists on the subject, viewed, as always, from the lens of my personal experience. This is a mega deep-dive and you can see the Key Findings first, and jump directly to topics in the Content, below.

Reading Time: 35m 20s

Words: 8,406

Key Findings

1) Procrastination affects 15-20% of all adults in the US, and men and women differently.

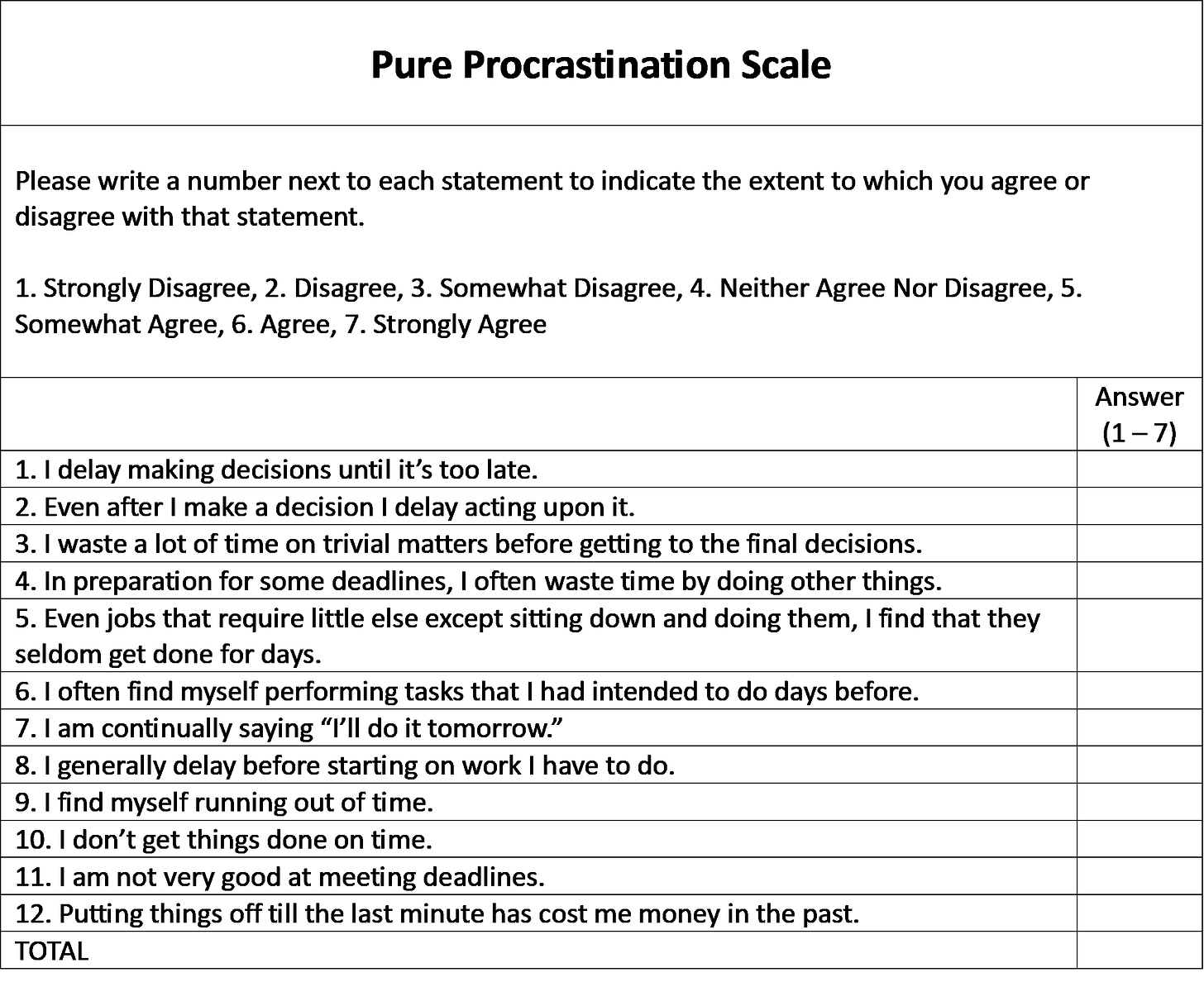

2) Procrastination can be measured using the Pure Procrastination Scale.

3) The FBM identified three core motivators and six simplicity factors affecting our action threshold.

4) New research has validated The Getting Things Done System and elaborated the process workflow clarifying actions, decision points and external memories.

5) Both the FBM and Elaborated Getting Things Done System are useful frameworks for thinking about your thinking, or acting on your inaction by investigating the cause and suggesting ways forward.

CONTENT

2. How prevalent is Procrastination in society?

3. What causes procrastination?

4. How can you measure how much you procrastinate?

5. The Pure Procrastination Scale

6. My Results on the Pure Procrastination Scale

7. The PPS Score Interpretation Table

8. The Top 10 Strategies, supported by research, to overcome procrastination

10. The GTD (Getting Things Done) System

11. Conclusion

1. What is Procrastination?

The word “procrastination” means to prefer the next day, coming from the Latin ‘pro’ meaning ‘forward, forth, or in favor of,” and “crastinus,” meaning “tomorrow”[3]

Which is easier said than done, because this time delay may be the behavioural manifestation of underlying irrational causes which is why procrastination is usually conceptualized by researchers as, “an irrational tendency to delay required tasks or assignments despite the negative effects of this postponement on the individuals and organizations.”[4]

The problem is procrastination can be both harmful to your own psychological, physical and financial well-being, as well as to others who count on you.

2. How prevalent is Procrastination in society?

Procrastination is highly common among students (80-95%), with three-quarters identifying themselves as procrastinators, and half procrastinating “consistently and problematically”. Students typically report that it claims over a third of their daily activities through sleeping, playing or watching TV.

But it isn’t just students, in the US procrastination affects 15-20% of all adults, and over 90% want to reduce it[5].

McCown and Johnson (1989) found that “over 25% of subjects stated that procrastination was a “significant problem” in their lives” and “almost 40% of subjects stated that procrastination had personally caused them financial loss during the past year.”[6]

And procrastination costs US taxpayers approximately $400 per return, due to errors from rushing to meet the deadline, and this equated to an overpayment to the government of $473m in 2002.

More worryingly, according to another study, most Americans haven’t saved up for their retirements due to procrastination:

“At least 80 percent of Americans have put off saving for their retirement so long that they no longer can realistically make up for their procrastination.”[7]

Interestingly, procrastination reaches a peak in the mid to late twenties for men, and then falls until mid-fifties, whereas for women it falls from the age of 20 until more or less stabilizing between 45 and 55, but then for both sexes, begins rising from 55 (see graph below)[8].

In terms of the wider effect of procrastination on businesses, in the UK, according to a survey of 2,000 workers by musicMagpie, procrastination costs businesses over £21 billion each year.[9]

3. What causes procrastination?

Firstly, procrastination is positively correlated with impulsivity, and both are heritable, 46% and 49% respectively, and variation in goal-management ability accounts for the difference.[10]

The correlation with impulsivity may explain why although we intend to do work, we suddenly change our mind to do something more enjoyable instead. This is consistent with neurobiology because the prefrontal cortex is primarily responsible for long-term intentions but these can be overwhelmed by impulses from the limbic system.[11]

“We are putting off tasks with long-term rewards because we are impulsively distracted by short-term temptations.” Steel (2010).

Steel (2022) has more recently also suggested that task aversion, fear of failing and perfectionism may also be the cause of procrastination.[12] We will return to a strategy to resolve this shortly.

Procrastination may also be due to self-regulatory failure relating to short-term mood repair and emotion regulation[13]. If you are contemplating an aversive task, it may make you feel anxious or stressed and the way to relieve this is not to do it, or task avoidance, which will immediately provide relief. (I assume the more often you do this, the better you will feel, almost like a self-reinforcing downward spiral, but this is not claimed in the research.)

In a study by Tice et al (2001), though, participants who were artificially put in a negative mood did spend more time procrastinating, by not preparing for the next task in the study, and they concluded, “Even a seemingly artificially induced negative mood proved to be enough to make people postpone an important self-control goal”[14].

In other words, when we are upset, we do something else, impulsively, to make us feel better, which is the same as prioritizing short-term mood, or affect, over other self-regulatory goals, which is why it is known as self-regulatory failure. Presumably, the more impulsive you are as a person, the worse this effect will be and the more you will procrastinate, thus the correlation found above, between impulsivity and procrastination.

Further, isn’t it reasonable to project from this, and again, I am going beyond the research, that if you are suffering from anxiety or depression, you will be more likely to procrastinate, which ironically, may make the anxiety and depression worse?

“Stress is magnified when we procrastinate. We anticipate being criticized not only for our work but for turning it in late; we tempt fate by pushing limits; we expect the worst to be waiting right around the corner; we feel guilty for disappointing, inconveniencing, or irritating others. It’s a vicious circle: procrastination produces stress, and stress can produce procrastination.”[15]

Further, in a study of 342 college students, Solomon and Rothblum (1984) found that procrastination “correlated significantly with depression, irrational beliefs, low self-esteem, anxiety and poor study habits”.[16]

Therefore, there are many different causes of procrastination which may be different according to the individual and their circumstances.

But how do you know how bad your procrastination is? Is there a way of measuring it?

4. How can you measure how much you procrastinate?

The best method to measure procrastination is the Pure Procrastination Scale created by Piers Steel (2010) [17] because it has “improved validity over previous instruments” [18] and has been used to measure procrastination using a 7-point Likert scale self-report measure.[19]

Complete the questionnaire below to determine how much you procrastinate scientifically.

5. The Pure Procrastination Scale

The realisation that I had been procrastinating, despite of all the evidence, didn’t sink in until I actually rated these questions. There may be a knowledge gap between what I told myself and the reality, so trust me, you should try answering the questions, like me!

To encourage you, let’s look at my results, and shoosh(!) don’t tell anyone else, this is just between us!

6. My Results on the Pure Procrastination Scale

This is me being as honest as possible, otherwise these instruments are meaningless, but at least you don’t have to show the whole world your scores! But what does this ‘total’ figure actually mean?

7. The PPS Score Interpretation Table

Normative data for comparison is hard to find, so you can use the following PPS Score Interpretation Table to interpret your scores, but note this is not research-based and only a rough non-medical guide I created based on the following estimated Mean and SD:

In research using a 5-point scale, the mean PPS score is typically 36 with an SD of approx. 7 -8.

Therefore, using a 7-point scale:

Estimated Mean: (36/5) x 7 = approx. 50

Estimated SD: (7/5) x 7 = approx. 10

The intervals in the range have been chosen to broadly reflect psychometrically valid ranges using standard deviation (SD) bands, rather than evenly distributed cutoffs.

Reading from the table, my procrastination score of 65 is high procrastination, and as a consequence, I did, like it states, “experience stress and/or anxiety”. Both.

Since we estimated from previous research using a 5-point scale that the mean score was 50 and the standard deviation was 10, we can calculate how many standard deviations my score deviates from the mean using the formula:

Z = (Your Score – Mean) / Standard Deviation.

In my case, Z = (65-50)/10 = 1.5.

A Z-Score of 1.5 means my score is 1.5 Standard Deviations above the mean, which means my level of procrastination is significantly above average, but not at the extreme high end or potentially chronic procrastination. I fall into the “High Procrastination” range (between +1 SD and +2 SD), which means it could be affecting my productivity, stress levels and/or well-being.

With this result I need a strategy to overcome my procrastination but what strategies are actually supported by research? After this we will try and integrate our understanding of how individual strategies might fit into an overall framework for conquering procrastination using the Fogg Behaviour Model and the Getting Things Done System.

8. The Top 10 Strategies, supported by research, to overcome procrastination

8.1. Address the Root Causes of Your Procrastination

Procrastination is often linked to perfectionism, task aversion, or motivation deficits (we will return to motivation in our focus on the Fogg Behaviour Model). For example, Steel (2007) found that procrastination is mostly a failure of self-regulation, relating to boring or aversive tasks and impulsivity[20], which we discussed earlier. Understanding your reason for procrastinating may help in choosing the right intervention.

If you procrastinate due to perfectionism, or fear of failure, it may help to try setting "good enough" standards rather than aiming for perfection. I think my procrastination may in part be due to perfectionism, rooted in a fear of failure, when related to writing these posts.

I am so desperate to succeed due to financial difficulties, I may be unconsciously frightened to fail and, ironically, procrastinating because I have an unrealistic expectation that my work must be ‘perfect’ to succeed.

If you are anything like me, we need to set realistic expectations and remember that anyone’s first draft isn’t going to be as good as their last, and that there is a point at which any further work on a draft, stops adding value in proportion to the time employed.

8.2. Use the “10-Minute Rule” to Overcome Task Avoidance

One of the hardest parts of overcoming procrastination is getting started. Research by Zeigarnik (1927) showed that we experience cognitive tension when a task is unfinished so we are more likely to finish it[21]. Indeed, it is more difficult to forget about an incomplete task than a completed task, which is known as the Zeigarnik effect. So, if we can only get started, we have a better chance of finishing the task.

Sometimes we may avoid an aversive task, not because the task itself is necessarily aversive, but the timeframe (we set ourselves!) required for the task, may be many hours, which is overwhelming, and that alone makes the task aversive. Which is why I suggested researching a reasonable timeframe on AI earlier!

One theory is that if we can handle ten minutes, however hard the task may or may not be, then we can make an informed decision, based on information gathering, rather than procrastination, about whether to continue after that, which may not be to the task’s completion, but at least allow you to make headway.

This is known as The 10-Minute Rule (often erroneously and countless times referred to online as the 5-minute rule without any source!) and was originally intended to help adults with ADHD[22]. It is simply having a goal of working on a task for just 10 minutes. After that, you can stop the task if you want.

But, according to the Zeigarnik effect, you will not want to! This may also lower your mental resistance to an aversive task, because starting is often the hardest part. Set a countdown timer for 10 minutes and if you complete it, you win! Even if you don’t continue working after that you have achieved your goal. Mission accomplished!

If you still find it difficult to start with the 10-minute rule, you can use the 5-second rule, which is just a trick to get around talking yourself out of doing something: Simply count down from 5 and start the 10-minute timer as soon as you hit 0!

8.3. Implement the “2-Minute Rule” for Small Tasks

Created by David Allen, author of “Getting Things Done”, the Two-Minute Rule states, “If it takes less than two minutes, then do it now.”[23] We will consider his system in more detail later.

This rule may help remove small, accumulating tasks that may be overwhelming. However, it may also be the start of something bigger, in the form of habit creation, which is useful if the task you are procrastinating is a regular occurrence like exercise, yoga or meditating.

James Clear cleverly adapts the Two-Minute Rule to habit creation when he writes, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”[24]

Clear explains that if you can’t “show up”, you can’t “master the finer details”.

And you can tie habits together sequentially so they become a routine. I do this for my morning routine, which involves a breathing practice (see WWH Breathwork) meditation (see WWH Meditation) and yoga (see WWH Yoga, coming soon!!!)

8.4. Break Big Tasks into Micro-Tasks

If you procrastinate due to task aversion, it may help to try breaking big tasks into smaller, more manageable parts or micro-tasks. There is research to support this.

A study by Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973) identified the availability heuristic[25], which is a cognitive bias that results in irrational or false conclusions. If we remember events relating to something easily, we assume it is more likely to happen. For example, if we see a car crash on the motorway, we may remember other car crashes on the motorway and assume the risk of a crash on a motorway is higher than it really is. But how does the availability heuristic apply to procrastination, you may fairly ask.

Firstly, we may wrongly estimate the difficulty of a task because we remember recently failing similar tasks (rather than our successes!) because of the availability heuristic.

Secondly, if you break tasks into smaller tasks, you may perceive each micro-task as easier, because you remember completing similar small tasks successfully due to the availability heuristic.

I have applied this technique to D.I.Y projects because I am hopeless at D.I.Y. and almost have an aversion to tools and ladders before I begin an aversive task! I literally wrote down all the steps, in order, in my free Microsoft To Do app. Which allowed me to break down the big task “How to Hang a Net Curtain” into micro-tasks, see box below, and I ticked off each one as I completed it on the app. I made it so easy a child could do it, and it was actually a breeze, when tackled like this!

If you don’t know the necessary steps to write down, there may be a knowledge gap, which is preventing you from completing the task. It sounds obvious, but I didn’t think of watching a YouTube video on how to do it, while the task was sitting on my task list for weeks, before I finally did!

Another tip is to ask for advice from AI, particularly with regards to a reasonable time frame to complete the task. There are several free apps I use for research including Perplexity, ChatGPT and Google Gemini. You need to double-check your results, and a quick way of doing this is to use one AI app to check another, although they could still both be wrong! So, always, if possible seek an expert opinion, ideally from primary sources, or for more practical DIY matters, YouTube! For a small monthly cost, and no I am not sponsored by them, you can even add ChatGPT to Alexa to make it easier to ask verbally. The Google Gemini mobile app also offers verbal enquiries.

If you struggle with motivation, it may help to use ‘temptation bundling’ (pairing a task with something enjoyable, like listening to music). I often ask Alexa to play music to accompany tasks, but more often with routine tasks, like writing this, rather than something I really struggle with, like hanging a net curtain! Music would have been too much of a distraction.

AI TIP: You could even ask AI (ChatGPT, Gemini, Perplexity, MS Copilot) to prepare timed manageable steps for you at your level of difficulty. For example, “How to hang a net curtain in 14 timed easy steps for beginners”, or do an internet search for the same question.

8.5. Use the Pomodoro Technique for Focused Work

The Pomodoro Technique, named after Francesco Cirillo’s tomato-shaped kitchen timer (Pomodoro means tomato in Italian 🍅) involves breaking down a long-timed task into more manageable shorter-timed tasks, usually of 25 minutes, with a 5-minute break in between, four times, before a longer break of 15-30 minutes[26]. How does this help overcome procrastination?

In psychological terms, it can improve cognitive endurance and reduce decision fatigue.

For example, it may make big tasks seem less daunting. The countdown timer for each shorter-timed task may also create a sense of urgency to improve focus. And taking regular breaks may be rewarding and positively reinforce a sense of achievement increasing motivation to complete the task.

Having short, focused and structured sessions can also help overcome what Boice (1989) termed “bingeing” as a work pattern; when you avoid work for a long time and then have intense marathon-like sessions, which can lead to burnout and create a downward spiral of procrastination.

The pomodoro technique may also help overcome what Boice termed “Busyness”; the tendency for procrastinators to engage in busywork or work of no practical use or value[27].

App Tip: There are many apps you can use to help you time your sessions and breaks. The Pomodoro Timer is a lightweight pc app from Francesco Cirillo, offered on a free donation basis. For a more immersive pomodoro experience, with external accountability, see more next, there is the Sukha app.

8.6. Set Up External Accountability

A study by Ariely and Wertenbroch (2002) found that self-imposed deadlines are not as effective as evenly spaced externally imposed deadlines, although these were least liked by participants[28]!

It is easier to be externally, or socially accountable, when you are at work and physically surrounded by colleagues or having face-to-face meetings but obviously harder when you are working alone, like I am writing this (!), or remotely.

The question is how can we set ourselves “externally imposed” deadlines, if we are suffering with procrastination in their absence?

We could share our deadline for a task with family or friends, or publicly on social media, to create external accountability. If that sounds too much like mixing work and pleasure, you could find an accountability partner and set up regular check-ins to increase your commitment to goals and reduce your procrastination. But where do you find one? Other work colleagues working remotely is one source.

However, there is also an app which may help reduce procrastination by increasing your external accountability by virtually working online ‘with’ others—watching others like you working at the same time on their webcams—combined with the Pomodoro technique, see above, called Sukha.

It feels like you are working with others in real time, although you are working alone. And others can see what task you are working on if you describe it, and even congratulate you when it’s done! But not before, or during, your task, which is important (see the findings on the damaging effect of interruptions next!)

It is great if you’re working remotely, or a writer on Substack like me, and I have met other Substack writers on there (Hi Nik!) and you can try Sukha for 14 days free here without a credit card, and then it’s £10/month, and if you want to get a 20% lifetime discount, use the code “GETFOCUSED” at checkout.

I find it also helps me relieve feelings of isolation and loneliness when I am working alone (Subscribe for free below not to miss WWH Loneliness coming soon!!!)

8.7. Adjust Your Environment for Success

A study by Mark, Gudith and Klocke (2008) found that interruptions caused participants more stress, higher frustration, time pressure and higher effort but, interestingly, didn’t affect the quality of the outcome, which was often completed in less time[29].

However, they found that it took participants 23 mins and 15 seconds on average to return to their original task, often after doing two different tasks first, which presumably, if repeated with each distraction, could eat up a lot of working time during your day. For example, I often find my work interrupted by notifications on my phone, do you?

The Sukha app, discussed above, has a QR code link which you can scan with your phone, to disable your phone during tasks so you are not distracted. Or you could simply turn your phone off (Shock horror!!! Now there’s a revolutionary thought!)

Or if you find yourself distracted by accessing websites on social media, gaming or video streaming platforms you could use website blockers like Cold Turkey or Freedom.

8.8. Reward Yourself Immediately for Completing Small Tasks

A study by Woolley and Fishbach (2018) found that people who receive immediate rewards for completing small tasks had increased intrinsic motivation and perceived the experience more positively, although interestingly not more important, than those receiving a delayed reward[30].

This doesn’t need to be a monetary reward. It could be as simple as treating yourself to a cup of tea or coffee, or allowing yourself 5 or 10 mins reading or browsing your favourite app.

I have also tried Habitica which is a pc and mobile app that virtually rewards you with gifts for completing tasks of varying difficulty you set yourself. This is great fun, but requires a little bit of work to set up your tasks, ironically, distracting you from actually doing them! It didn’t work for me, but it may work for you.

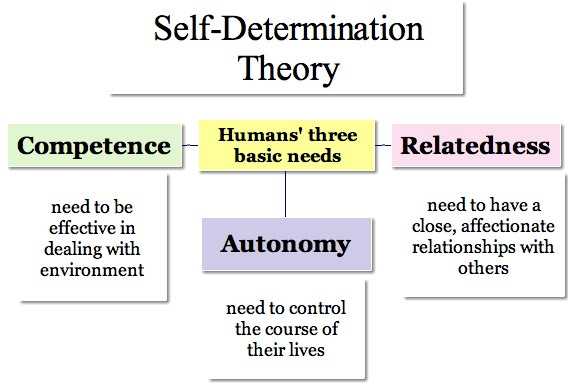

However, it is worth noting that if you lack intrinsic motivation according to Ryan and Deci (1985), you may not be meeting your needs for Autonomy (feeling in control over your actions and decisions), Competence (feeling capable and effective) and Relatedness (feeling supported, understood and valued) [31].

I think this is important because I have definitely experienced procrastination for certain tasks that I didn’t feel I had the agency—read competence, autonomy and relatedness—to complete, even though I was quite capable. I didn’t feel empowered enough to do the task, in spite of being physically able and it felt like I wasn’t emotionally able. Don’t let others prevent you from doing what you think is right. Even counsellors see counsellors as a requirement of their practice, so don’t hesitate to seek professional guidance if you need help in this area.

9. The Fogg Behaviour Model

The Fogg Behaviour Model (FBM) (2009) eponomously named after Brian Jeffrey Fogg, attempts to explain what causes people to take action[32], and it was intended to inform persuasive techniques like advertising but I also think it may be applicable to procrastination, and it may make you look at your procrastination in an entirely different way. It did for me, at least.

The FBM claims that action is the result of three varying factors: 1. Motivation, 2. Ability and 3. A trigger, which Fogg plotted on a graph, see below, to show how they influence achieving target behaviour:

Therefore, if we want to complete a Task we have been putting off, we need to consider what motivates us, our ability to do it and identify a suitable trigger. The trigger will depend on our level of motivation combined with our level of ability, and if neither are high enough in combination to cross the threshold for action, the prompt, or trigger, will not work. We can see this represented diagrammatically below. The trigger needs to be anywhere right of the curving Action Line.

Fogg explained that we need to identify the following dimensions within each of the three factors 1. Motivation, 2. Ability and 3. Triggers.

1. Three Core Motivators:

i) Pleasure/Pain. Primitive response, and result immediate. Eg. Hunger, sex, self-preservation. There may also be intellectual or emotional pain associated with a task you may be procrastinating, and this will reduce your motivation to complete it.

ii) Hope/Fear. Anticipating good/bad outcome. Eg. Hope-Join Dating site / Fear-Install Virus Software. We have already mentioned above how Perfectionism and Fear of Failure may influence procrastination and in the FBM we can clearly see how this would lower motivation to do the task, regardless of the dimensions of ability, which we will consider below.

iii) Social Acceptance/Rejection. Motivation to be socially accepted, or avoid rejection. Eg. Facebook. One way of increasing motivation and use this dimension to avoid procrastination is by sharing your task with a partner or friend, or on social media.

2. Six Simplicity Factors that influence Ability:

i) Time. If a task takes more time, it is not simple, and increases in complexity, reducing our ability to do it. (Lower ability would obviously be marked left of the x-axis on the graph.) Our estimation of time for a task, as explained above, may influence our level of procrastination, which is why it is important to have realistic estimates for the total task, and set realistic goals for achievable completion. For example, rather than a task of 6 hours being scheduled for one day, break it down into 3 x 2hours a day.

ii) Money. If a task costs more to do, it is less simple, and more complex, reducing our ability to do it. If this is a factor in your procrastination, it would be better to abandon the task, or reschedule it to a later time and place, than leave it hanging. Or redesign the task to accommodate the time and resources available.

iii) Physical Effort. The greater the physical effort required, the lower our ability to do it. If this is causing you to procrastinate, try using different tools or planning around it. For example, rather than walking from London to Edinburgh, catch a train or a plane.

iv) Brain Cycles. If a task causes us to “think hard” that may not be simple, and more complex. Fogg claims that, “we tend to overestimate how much everyday people want to think. Thinking deeply or thinking in new ways can be difficult.” If I am honest, I think this dimension is a factor when I was procrastinating the completion of at least one of my blogs. Sometimes it can be intellectually challenging to research topics and interpret primary research, especially in a number of different fields. My way of overcoming this was to find the excitement and enjoyment again in a new topic, and make a conscious decision to return to the other topic when this was completed.

v) Social Deviance. Fogg describes this dimension as, “going against the norm, breaking the rules of society. If a target behavior requires me to be socially deviant, then that behavior is no longer simple.” He gives the example of wearing pyjamas to a council meeting and the subsequent social price paid for flouting convention, increasing the complexity, and reducing our ability to action that behaviour. If you are procrastinating about a task that involves a moral or social complexity, like getting a divorce, which may be frowned on, it may be useful to reflect on the extent to which the consequences are real or imagined, and how any emotional pain can be minimised, perhaps, by sharing information or seeking support.

vi) Non-Routine. A non-routine increases complexity, reducing our ability to action it. When a task becomes a routine, it is relatively simple to action, which is why I suggested above that the 2-minute rule may be usefully adapted to help avoid procrastination by making an action a habit.

The key point about all the dimensions of simplicity is that, “Simplicity is a function of a person’s scarcest resource at the moment a behaviour is triggered.” Before we consider the three dimensions of behaviour triggers, which are what tell people, or we prompt ourselves, to perform a behaviour now, it is worth mentioning that it is probably more effective to increase simplicity, than increase motivation in this model, which I think is particularly true when it comes to procrastination.

“In General, persuasive design succeeds faster when we focus on making the behaviour simpler instead of trying to pile on motivation. Why? People often resist attempts at motivation, but we humans naturally love simplicity.” Fogg (2009)

3. Three Behaviour Triggers.

When you have the necessary motivation and ability, a trigger is all that’s needed to start the task, but not all triggers work in the same way. The three dimensions of triggers are:

i) Spark. When motivation to complete a task is low a trigger could be designed with an element of motivation. For example, thinking back to the second of the three motivators, above, hope/fear, a spark could be adding a note to the task on your Todo app/list like a warning, eg. Task: Complete Tax Return. (Added note: ) Failure to comply £X Fine. Or, for hope, recording a selfie video for self, or partner/friend, sharing you have a tax return to complete before Friday, and promising a treat if it is done.

ii) Facilitator. This trigger may be useful when you have high motivation to complete a task but lack ability. As Fogg explains, “The goal of a facilitator is to trigger the behaviour while also making the behaviour easier to do.” For example, if you are procrastinating a task because it is too complex, like for me, hanging a curtain, you can break it down into smaller steps and add these to your Todo app/list, as described above.

iii) Signal. This type of trigger works best when you have the motivation and ability to complete the task and all you need is a reminder. The signal doesn’t aim to motivate or simplify the task, just inform you what needs to be done at the right time. For example, a traffic light at a pelican crossing, which is activated when people need to cross the road. In order to avoid procrastination, when you have the motivation and ability to do a task, you need to set a timely reminder and that should be enough. For example, a notification in your calendar app should be sufficient. I often set my google calendar to send me an email notification 4 hours before, or a notification to the home screen an hour before, a task needs to be undertaken.

The factors, and dimensions, of the Fogg Behaviour Model are therefore useful in identifying problems causing you to procrastinate, and failing to complete intended tasks, and hopefully suggest systematic ways to overcome this.

10. The GTD (Getting Things Done) System

Another way to positively think about tasks you are procrastinating is what would be great?

Or as David Allen puts it, “Wouldn’t it be great if . . .” is not a bad way to start thinking about a situation, at least for long enough to have the option of getting an answer.”

David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, starts his book by asking you to visualise the successful outcome of one task and identify the first step[33]. We may add tasks to our to-do list eg. Hang curtains, to an ever-growing list, but without clearly perceiving the benefit of doing this, we are just increasing the burden, and not getting things done.

“Getting things done requires two basic components: defining (1) what “done” means (outcome) and (2) what “doing” looks like (action). And these are far from self-evident for most people about most things that have their attention.”

Allen suggests that as soon as your to-do list reaches two in your mind, you’ve already created personal failure because you can’t do both at the same time.

Before we consider the system, it is important to note that there is independent research to support the effectiveness of the Getting Things Done system, which we will identify below, because it is not just another self-help book, that although well-meaning may lack academic authority. The theory behind the system has been supported by cognitive science[34].

So, let’s briefly consider how David Allen’s system works to see whether it can help you as much as it helped me.

There are five steps to manage the horizontal aspect of our lives, everything we need to do—in contrast to the vertical aspect, which is only considering one task in depth—Capture, Clarify, Organise, Reflect and Engage.

Let’s briefly consider the key aspects of each step in case you want to implement the system.

Step 1. Capture

Collect each task on your mind physically, eg. letters, reports, articles, notebooks, etc., and digitally, eg., emails, texts, mobile apps, and write each task on a separate piece of A4 paper, like a placeholder. You can add information to the A4 paper, which is important later.

“You can only feel good about what you’re not doing when you know everything you’re not doing.”

Do not do anything about this stack of tasks on paper, however tempted, the goal of the system is to process them effectively, and train yourself to do this systematically and periodically.

If you want help identifying items, or you want to make sure you have captured everything in your life, you can subscribe for free to Whichwayhow.com and download the “Getting Things Done Life Inventory -Triggers List” pdf in the welcome email! (If you’re already an existing free or paid subscriber, you don’t have to do anything, you will find this as an attachment to this newsletter when it was emailed (another great reason to subscribe free below and not miss out on time and money-saving posts like this one!)

But you really don’t need this pdf to practice the GTD method, and you can also find it in David Allen’s book at your local library, or from Amazon here. It is basically just an 8-page list of triggers to help you remember everything that may be either on your mind or nagging away at the back of your mind that I haven’t got room for in this post, but I still personally found useful.

When collecting items for your inbox you are looking for “all the things you consider incomplete in your world—that is, anything personal or professional, big or little, of urgent or minor importance…” but David Allen’s inspired conclusion is this “…that you think ought to be different than it currently is and that you have any level of internal commitment to changing.” [My italics].

I think it is easy to forget that our procrastination is only an issue when we think some aspect of our lives should a) be different, and, b) we want to change it. This is like going back to first principles. If not, just trash it!

Step 2. Clarify

Process what each item means, and what to do with it; what to keep and what to throw away (see Original Getting Things Done Process Flowchart, below).

The “Getting Things Done Process Flowchart (Elaborated)” is an elaboration of the one in David Allen’s book, by Heylighen and Vidal (2008) which I think is clearer by clarifying actions (rectangles), decision points (diamonds), external memories eg. lists, folders, files (stacks), see below.

Further, the connecting lines have specific meanings: a) continuous arrows indicate the immediate sequence of processing, b) broken arrows indicate delayed processing during a review of external memory, c) dotted lines indicate follow-up processes[35].

This is important because when I think about why I was procrastinating while there may be an emotional element, with this elaborated model I can clearly see it could be a decision-making ‘fault’ or block (rectangle), because I wasn’t clarifying the action needed, but rather trying to do all five processes at once.

Work down from the top of your “in” tray, and process each item, which doesn’t mean start thinking about solving it, just decide what to do with it. If it isn’t actionable right now, a) Bin or delete it, b) Add it to Someday/Maybe File/List (manually or digitally), c) Add it to your Reference system (Printed Label Envelope Files, alphabetically ordered, or Create Categories on Email, or on your favourite To-Do app, and add digitally.

“The cognitive scientists have now proven the reality of “decision fatigue”—that every decision you make, little or big, diminishes a limited amount of your brain power. Deciding to “not decide” about an e-mail or anything else is another one of those decisions, which drains your psychological fuel tank.” – David Allen

If an item is actionable right now, a) Do it now (if it will take less than 2 minutes), b) Delegate it (Add to ‘Waiting’ list, c) Defer it, i) Add to Calendar ii) Add to “Next Actions” list, to do asap.

Step 3. Organise

Organise what you keep – when are you going to act on it? Short-term – now, this morning/afternoon, or, long-term, next week, month and set a reminder.

Step 4. Reflect

Reflect on the options, periodically and systematically review current and planned tasks to ensure that new tasks don’t suddenly hijack the agenda!

Step 5. Engage

Engage with the right task at the right time. Do it!

“A task left undone remains undone in two places—at the actual location of the task, and inside your head. Incomplete tasks in your head consume the energy of your attention as they gnaw at your conscience.” - Brahma Kumaris

11. Conclusion

This deep dive on avoiding procrastination has considered: the definition, prevalence and causes of procrastination; how you can measure procrastination using the Pure Procrastination Scale and interpret your results with the PPS Score Interpretation Table; the Top 10 strategies, supported by research, to overcome procrastination; and two frameworks for rethinking procrastination in The Fogg Behaviour Model and the Getting Things Done System.

As so often is the case, there is not necessarily one best way, because it varies from person to person, but hopefully by considering the main ways to overcome procrastination, supported by over thirty primary references (see below), you will have found a cause and strategy that resonate with you.

For me, procrastination sometimes varied by task, for example, procrastinating about completing a post or making a dentist appointment had entirely different causes; the former was caused by perfectionism and fear of failure and the latter by a psychological or emotional reason, that is, fear (see The Self-Determination Model, above). The cause will determine the strategy you use to overcome your procrastination about a task.

The next time you find yourself procrastinating, or putting off something to do something else, it may help to, firstly, be mindful of when this is happening, secondly, to consider the cause. To identify the cause, it may help to identify which stage, or action, you are struggling with in the Getting Things Done System, above, eg. Clarify, Organise, or a Decision-making stage, like, “Is more than one action needed?” Try and visualise the flowchart in your head to see where a blockage may be.

Or is your procrastination related to one of Fogg’s three core motivators or six simplicity factors, for example Pleasure/Pain? And if so, what is causing that, for example, what is that pain related to? Applying Self-determination theory, is it possible that one of your needs is not being met, for example, Autonomy, Competence or Relatedness. These may lie at the root of your problem. If you can identify it, you are half-way to solving it. Then implement one of the Top 10 Strategies, supported by research, above, that is most applicable. If the strategy you selected doesn’t work try unpeeling the onion, so to speak, and considering the underlying cause.

In the same way that getting a job is like a job, with procrastination, you just have to do it—that is investigate doing it—to get it done. Don’t struggle with your to-do list and barely survive, thrive in leaps and bounds with your to-do list, and start generating that upward spiral of positive reinforcement.

This is how I successfully overcame my procrastination to write this blog, and got my passion for writing back! And not only this, I have even finished WWH Gratitude and WWH Loneliness which will be published in the next two consecutive fortnights! Thrive-to-do!

I hope you found this post helpful in conquering your procrastination and good luck on your procrastination-free journey!

Thank you for reading.

If you’d like to buy me a coffee you can do so below:

Please share this article to help others:

And if you don’t want to miss the next deep dive in a fortnight which may be just what you need to solve another problem, subscribe below.

References

[1] Farnham, B. R. (1997). Roosevelt and the Munich crisis: A study of political decision-making. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. See also, Kegley, C. W. (1989). The Bush administration and the future of American

foreign policy: Pragmatism, or procrastination? Presidential Studies Quarterly, 19, 717–731.

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/20/tump-executive-orders-list Accessed at 09:57 on 27th January 2025.

[3] Klein E.. (1971). A comprehensive etymological dictionary of the Hebrew language for readers of English. Tyndale House Publishers

[4] Yan B, Zhang X. What Research Has Been Conducted on Procrastination? Evidence From a Systematical Bibliometric Analysis. Front Psychol. 2022 Feb 2;13:809044. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809044. PMID: 35185729; PMCID: PMC8847795. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8847795/

[5] Steel, Piers. (2007). The nature of procrastination: a meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol Bull 133: 65-94. Psychological bulletin. 133. 65-94. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65.

[6] McCown, w., & Johnson, J. (1989a, April). Validation of an adult inventory of procrastination.

Paper presented at the Society for Personality Assessment, New York.

[7] Steel, Piers. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist?. Personality and Individual Differences. 48. 926-934. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025.

[8] Ferrari, Joseph & Johnson, Judith & McCown, William. (1995). Procrastination and Task Avoidance--Theory, Research and Treatment. 10.1007/978-1-4899-0227-6.

[9] Cost of procrastination to UK businesses based on 261 working days each year, 24,213,000 full-time workers and an average wage of £28,677. Research based on survey of 2,010 full-time workers, ran with Censuswide in November 2019. https://www.musicmagpie.co.uk/paid-to-procrastinate/

[10] Gustavson DE, Miyake A, Hewitt JK, Friedman NP. Genetic relations among procrastination, impulsivity, and goal-management ability: implications for the evolutionary origin of procrastination. Psychol Sci. 2014 Jun;25(6):1178-88. doi: 10.1177/0956797614526260. Epub 2014 Apr 4. PMID: 24705635; PMCID: PMC4185275.

[11] Steel, Piers. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist?. Personality and Individual Differences. 48. 926-934. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025.

[12] Steel, P., Taras, D., Ponak, A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. (2022). Self-Regulation Of Slippery Deadlines: The Role Of Procrastination In Work Performance. Frontiers In Psychology, 12, 783789.

[13] Sirois, F. and Pychyl, T. (2013) Procrastination and the Priority of Short-Term Mood Regulation: Consequences for Future Self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7 (2). 115 - 127. ISSN 1751-9004

https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12011

[14] Tice, D. M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in

the context of general self-control. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 149-159. See also, Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53-67.

[15] Burka, Jane & Yuen, Lenora. (2008). Procrastination: Why You Do It; What To Do About It NOW. Jane Burka and Lenora Yuen 2008. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

[16] Solomon, L. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (1984). Academic procrastination: Frequency and cognitive-

behavioral correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 503-509.

[17] Steel P. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: do they exist? Pers. Individ. Dif. 48 926–934. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025

[18] Svartdal F, Pfuhl G, Nordby K, Foschi G, Klingsieck KB, Rozental A, Carlbring P, Lindblom-Ylänne S, Rębkowska K. On the Measurement of Procrastination: Comparing Two Scales in Six European Countries. Front Psychol. 2016 Aug 31;7:1307. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01307. PMID: 27630595; PMCID: PMC5005418.

[19] Validation of the Pure Procrastination Scale, Kiser, Monica Mae. California State University, Fresno ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2020. 27998580.

[20] Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94.

[21] Zeigarnik, B. (1927). On finished and unfinished tasks. Psychologische Forschung, 9(1), 1–85.

[22] Ramsay, J.R., & Rostain, A.L. (2014). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD: An Integrative Psychosocial and Medical Approach (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203375488

[23] Allen, D. (2001). Getting things done: the art of stress-free productivity. New York, Viking.

[24] Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: tiny changes, remarkable results : an easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. New York, New York, Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

[25] Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

[26] Cirillo, Francesco (2018) The Pomodoro Technique. Penguin Random House.

[27] Boice, R. (1989). Procrastination, busyness, and bingeing. Behavior Research and Therapy, 27(6), 605–611.

[28] Ariely, D., & Wertenbroch, K. (2002). Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: Self-control by precommitment. Psychological Science, 13(3), 219–224.

[29] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 107–110.

[30] Woolley, K., & Fishbach, A. (2018). It’s about time: Earlier rewards increase intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(6), 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000116

[31] Ryan, Richard & Deci, Edward. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. The American psychologist. 55. 68-78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. See also, Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

[32] Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology.

[33] Allen, David. (2015). Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-free Productivity. Penguin Books.

[34] Heylighen, Francis & Vidal, Clément. (2008). Getting Things Done: The Science Behind Stress-Free Productivity. Long Range Planning. 41. 585-605. 10.1016/j.lrp.2008.09.004.

[35] Heylighen, Francis & Vidal, Clément. (2008). Getting Things Done: The Science Behind Stress-Free Productivity. Long Range Planning. 41. 585-605. 10.1016/j.lrp.2008.09.004.